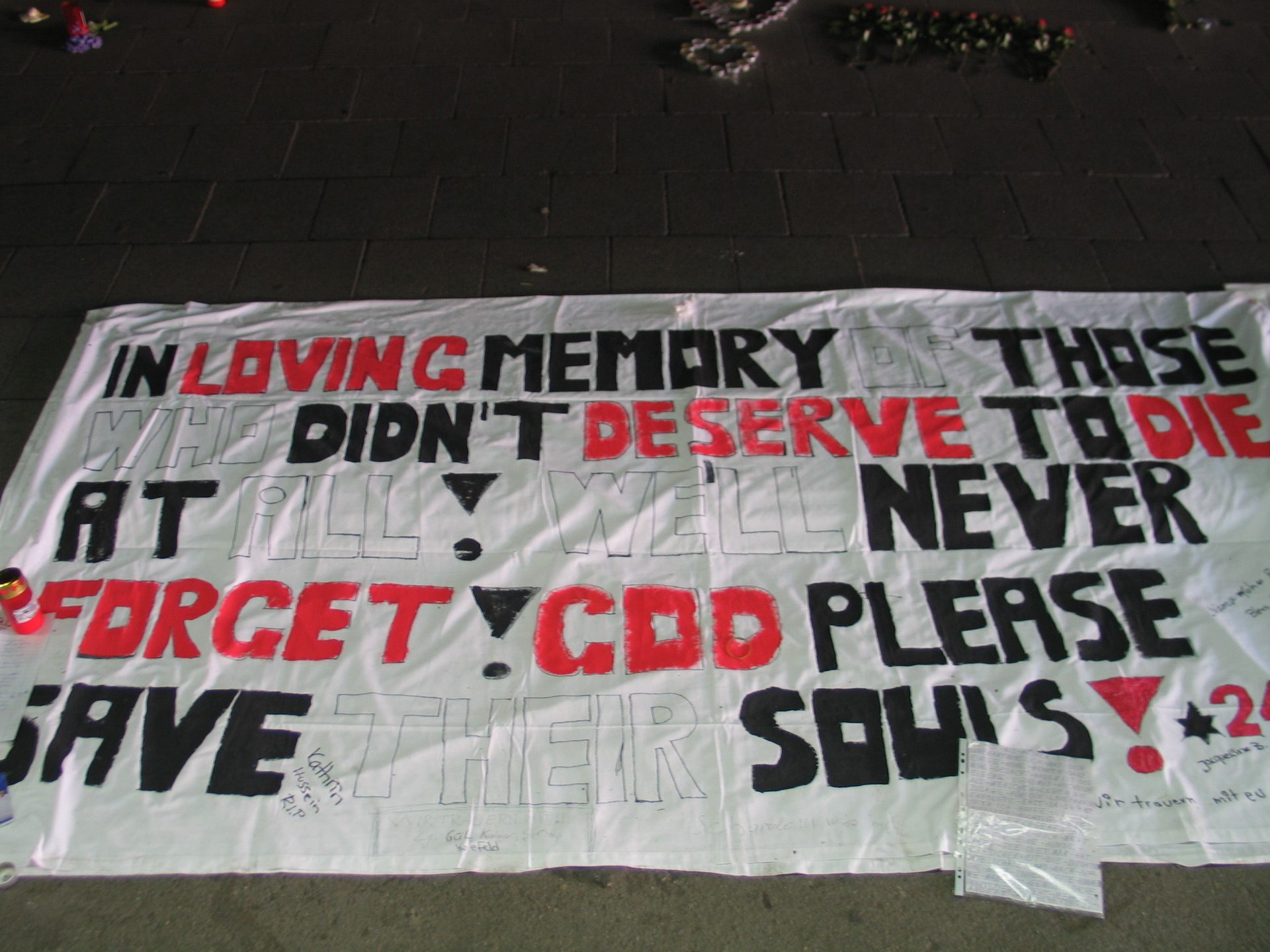

According to the media, nearly every mass accident involving crowds of people is immediately labelled a stampede. However, real-world incidents such as the Love Parade disaster (2010), the Hillsborough tragedy (1989), the Bergisel Stadium crush (1999), and the Seoul Halloween crowd crush (2022) tell a different story.

The assumed cause?

Mass panic.

But is this really the cause or is mass panic just a myth?

Let’s look into crowd behaviour when emergencies arise.

The Myth of Mass Panic

People are often portrayed as reckless, aggressive, and irrational in emergencies—pushing, jostling, and trampling others.

These reports suggest that victims are to blame for their own fate. Frequent media coverage reinforces the belief that mass panic is a common phenomenon (Drury, 2014).

Dombrowsky and Pajonk (2005) highlight how literature often describes crowd behaviour using phrases like “horses running through,” “herds breaking out,” and “fear and terror.”

These terms imply that individuals lose rational thought and become controlled by impulsive instincts.

Rather than identifying the actual causes, disasters are attributed to the so-called panicked behaviour of individuals.

As a result, politicians, emergency personnel, and law enforcement perceive mass panic as a significant risk that must be addressed in security planning.

“Stampede is not only an incorrect term, it is a loaded word as it apportions blame to the victims for behaving in an irrational, self-destructive, unthinking and uncaring manner.”

— Prof Edwin Galea, University of Greenwich (Lock, 2022)

Understanding Crowd Behaviour: From Panic to Reality

The idea of mass panic dates back to Gustave Le Bon’s Psychology of the Masses (1895).

He claimed that crowds possess a “mass soul,” which overrides individual decision-making and leads to impulsive, irrational behaviour.

Philosophers and psychologists, including Elias Canetti, Sigmund Freud, and Hermann Broch, further explored these ideas in the context of industrialisation and labour movements.

Dombrowsky and Pajonk describe crowds as “raging animals,” “subversive mobs,” or “revolutionary subjects of history.” Brickenstein suggests that panic spreads like a virus, affecting large groups instantly.

Media perpetuation of these ideas has led to continued misinterpretation of crowd behaviour.

However, research contradicts these myths.

Experts such as Dr John Drury (University of Sussex), Dr Keith Still (Manchester Metropolitan University), and Prof Dirk Helbing (ETH Zurich) provide a different perspective. They argue that:

- Mass casualties result from structural and planning failures, not panic.

- The behaviour of those involved in crowd incidents is largely rational, not chaotic.

Drury and Still emphasise that in the Seoul Halloween crowd crush (2022), panic was a consequence, not the cause, of the tragedy.

“People don’t die because they panic. They panic because they are dying.”

— Prof Keith Still, University of Suffolk (Lock, 2022)

“Videos of the Itaewon incident show fear and distress. But this occurred after the crushing had begun. It was a consequence, not a cause, of the disaster. ‘Panic’ is an unnecessary explanation. The psychology of the crowd was not abnormal; it was COMPLETELY NORMAL.”

— Prof John Drury, University of Sussex (Lock, 2022)

The Reality of Crowd Disasters

Empirical research shows that crowd disasters are not triggered by panic or selfish behaviour.

Instead, they result from planning failures in event design, information dissemination, and crowd management (Still, 2014).

Poor planning leads to dangerously high crowd densities, causing compressive asphyxia—a condition where excessive chest pressure prevents breathing, leading to suffocation.

“At what point did anyone in this crowd think ‘Let’s become a mob’? They didn’t—they reacted to the extreme density and could not escape, leading to a progressive crowd collapse and mass fatalities.”

— Prof Keith Still, University of Suffolk (Lock, 2022)

Densities above six people per square metre pose severe risks, leading to shock waves and crowd collapses.

Still and other researchers highlight that such incidents are often “reasonably foreseeable” and preventable through proper planning.

Crowd Behaviour in Emergencies

Studies of emergencies, such as the London bombings and the World Trade Centre evacuation, reveal that people generally act calmly and cooperatively.

Survivors frequently describe a sense of camaraderie rather than chaos (Drury et al., 2009).

Drury and his colleagues argue that in crisis situations, individuals form a “social identity,” shifting from personal to collective behaviour. Strangers become a unified group, working together to survive (von Sivers et al., 2014).

Rather than viewing crowds as a problem, Drury suggests they should be seen as a resource for collective resilience.

Implications for Event Safety

If mass casualties are foreseeable and panic is not the primary risk, what does this mean for safety planning?

- Risk assessment: Event venues must be analysed to identify areas prone to high crowd density during normal and emergency situations.

- Density management: Areas exceeding six people per square metre must be avoided.

- Communication: If crowding occurs, clear and rapid communication is essential to manage density and ensure safe movement.

- Public awareness: Visitors should be well-informed about venue layouts, emergency exits, and expected behaviour in emergencies.

- Evacuation planning: People tend to follow familiar routes during evacuations. Without proper guidance, this can lead to congestion at key exits, reducing flow rates and increasing risk.

- Efficiency in emergencies: Well-informed crowds react more rationally and efficiently in crises, reducing overall risk.

Extended evacuation times, particularly in life-threatening situations like fires, increase casualties. Therefore, effective communication and crowd management are critical to ensuring public safety.

Conclusion

Crowd disasters result from preventable factors such as poor planning and high-density areas, not irrational panic.

Understanding real crowd behaviour allows for better event safety strategies, ultimately reducing risk and improving emergency response.